|

Figure 1.

The panel screwed to the deck abaft the mast, requiring a slight bowing that is accommodated by the unit. Shadow thrown by the mast, boom and running rigging has not been found to cause significant reductions in charging. |

|

After two seasons of cruising our Sadler 34 with 150 Ah

of service battery capacity and 75 Ah of starter

battery, it was clear that we needed to do something

about keeping them fully charged. During a glorious

fortnight cruising in Cardigan Bay in 1996 we sailed

very short daily distances, often without running the

engine at all. Keeping supplies of butter and beer in

optimum condition required us to run the refrigerator

constantly, with the result that battery voltage rarely

staggered to 12.5 V and was more often seen at less

than 12.0 V. On some mornings we would wake (usually

quite late) with insufficient service power to drive

the fresh water pump or even to light a light bulb.

Perhaps as a consequence of this abuse, but possibly

due to a lifetime (however brief) of similar treatment,

we were forced to replace one battery in Aberystwyth at

a cost of £81. A later cruise to Scotland was

accomplished in far more temperate conditions, allowing

us to turn the refrigerator off at night, but we had

acquired a taste for cold drinks. Something would have

to be done!

The solution arrived in the rather drastic form of a job transfer to The Netherlands. On a very wintry weekend early in 1997 we attended HISWA, the Dutch Boat Show in Amsterdam. Several exhibitors were showing solar panels and we collected the usual stack of literature from each. The most appropriate for our purpose seemed to be a Sunware 2.0 Amp, 40-cell unit that will allow a certain amount of bending (3 cm per metre length) and could be walked upon when screwed down to the deck. 40-cell panels are intended to provide extra voltage to compensate for reduced output when hot, a serious flaw in design that demonstrates once again how the laws of physics conspire against yachtsmen. A couple of weeks later we visited the supplier, also in Amsterdam, and made our purchases. In addition to the panel we bought the cheapest controller available, an 8 Amp unit, with the future intention of adding more panels. On getting it home and translating the instructions we found that we would have been much better off with a more expensive unit (naturally) that switches from the service battery to the starter battery when the former is fully charged. So another trip to Amsterdam resulted and the unit was exchanged for a FOX-i90-2A, a 12 Amp unit that will certainly cope with anything we can ever hope to supply to it. |

|

Figure 1.

The panel screwed to the deck abaft the mast, requiring a slight bowing that is accommodated by the unit. Shadow thrown by the mast, boom and running rigging has not been found to cause significant reductions in charging. |

|

On a May visit home to prepare the boat for its voyage to Holland we fitted the units. We had decided to put the panel in one of the few available places on the coachroof, astern of the mast. Although this was likely to be in shadow for some of the time we chose to accept it as a compromise, not wishing to build a structure to give maximum exposure. 4 mm2, domestic multi-strand wiring cable was purchased to give the maximum possible cross-sectional area consistent with feeding it through some very small holes and passages. The longest run, about 6 metres, was made between the solar panel and the control unit, which was placed on the switch panel behind the companionway steps. Separate cables were led from the control unit to each battery connector on the main battery switch, a distance of only 30 cm. Finally the fuses were put in and we checked the digital ammeter on the control unit. Nothing! The job had taken such a long time that it was now dark. On awaking next morning we expectantly viewed the meter and found a healthy 0.4 Amp, rising to over 1.4 Amp by midday. We then left the boat until June. |

Figure 2. Wiring circuit supplied with the control unit |

Our next look at the meter was very encouraging; both service and starter batteries indicated almost 13.0 Volts. During the course of our three week cruise from Anglesey to Holland via Brittany the refrigerator was never off. Service battery voltage fell to about 12.3 volts during an overnight passage but recovered during the day. Occasional use of the engine in calm and to enter ports was sufficient to boost voltages to over 13.0 and we never ran the engine simply to charge the batteries. Since then we have enjoyed a remarkably hot summer during which we have spent every weekend, one four day weekend and a week's holiday on the boat, largely in temperatures above 30 degrees Celsius. |

|

The refrigerator has been on constantly during these periods, although we use shore power to reduce its temperature when we first arrive and stock it with food at the start of the weekend. We now use the engine very rarely, perhaps only for half-an-hour per weekend, yet the lowest service battery voltage yet seen has been 12.2 V. The starter battery voltage is a constant 12.8 V. The shadow of the boom is rarely a problem as we simply travel it to the appropriate side. Mast shadow probably accounts for a couple of hours per day but has no noticeable effect. |

|

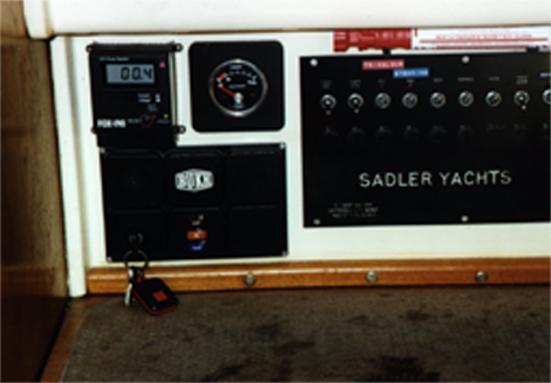

Figure 3.

The Fox-i90 unit, upper left, fitted nicely into the available space on the panel, although the wiring path was tortuous. Here it is reading a healthy 0.4 A around midday in early October. |

|

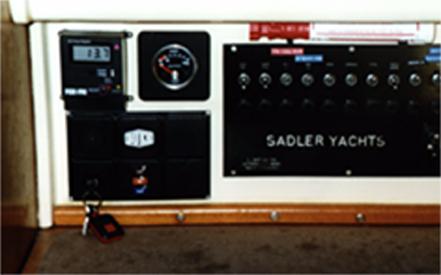

Figure 4.

The control unit in its alternative mode, showing voltage. Levels as high as the 13.7 V displayed occur only during or shortly after running the engine. |

|

It would not be possible to justify fitting such equipment solely on the grounds of battery replacement. The total paid for panel, controller and cable was nearly £400, enough to cover likely battery costs for years to come. Its advantage to us is the knowledge that batteries are always sufficiently charged for their purpose, that they will remain charged during the winter and unattended periods without the need for booster charging and, best of all, the avoidance of those lengthy periods of engine running at anchor. However, when looked at in terms of the considerable wear that engine bores suffer during the unloaded charging process, there may be another side to the argument. I just enjoy the quiet of the mornings and don't bother to think about it. |