Latest: [Read the latest story from Chris]

Next page: [A Winter's

Work]

A Starting Point

The idea of just going sailing - and not actually

continuing to work for a living - is one that has been with

me for a long time. But life, I convinced myself, kept

getting in the way.

When my first wife, Sandra, died very young, I already owned

a small cruising boat; a Pandora 22 footer. I talked about

sailing away for ever (or a few months) in that, but not for

the first or last time, I found myself an excuse for not

doing what I talked about.

That 'excuse' turned out to be a more-or-less unsatisfactory

marriage, which none the less lasted for nine years. I then

lived for another five years on my own, with various passing

girlfriends and assorted boats, until I married again, into a

four-and-a-half year disaster - although I didn't realise

what a disaster it was until about four years and five months

into it! The trouble is, I guess, that I have always believed

in the idea of marriage, although success in the day to day

achievement of it seems to have eluded me.

Also during that marriage, in fact only four months before

the end of it, I had a minor heart-attack. So, single again

at the reasonably ripe age of 52, I understood that life, or

perhaps God, was trying quite hard to tell me something. But

I also knew it would take me some time to work it all out. A

year down the line, with my general health seeming to be

pretty fair (touching wood and clasping the bottle of little

tablets), I started to think that I could have got it worked

out after all. The last wife and I had come to some sort of

agreement a few months before over finance, and like many

women in a separation, I felt that she'd managed to keep the

lion's share of our joint worth. After a lifetime of

reasonably hard work and approximate endeavour, I had what I

thought was a remarkably small amount of money, around

£30,000 in cash, stashed away in premium bonds and building

societies. So what good could that amount of money do me ?

Looked at from a conventional viewpoint, not very much. It

was a sufficient sum to preclude me from housing benefit -

and most of the rest of the benefit system - if I lost my

job; I'd have to spend about ten thousand pounds on surviving

and living before they'd even pay anything towards my rent.

With the job market the way it is, it didn't seem worthwhile

to plough the money into a house and carry on labouring away

to pay the mortgage; and if the job collapsed, then I'd only

have to sell it and effectively start all over again. If I

managed until the endowments paid it off, who would

ultimately benefit from that ? Only my legatees, and much as

I love my niece and nephew, I could not really see why I had

to give them everything. If I popped my clogs before the age

of 62 they'd do fine, and if I survived, then I'd get a good

deal more from the endowments with bonuses and whatnot.

The money could do me far more personal good as the funding

for an extended holiday, however. The sums were pretty

simple. I felt reasonably confident that I could afford a

small sailing cruiser or motor-sailer for around five to six

thousand pounds, live on it for a couple of years on fourteen

or fifteen thousand, and still come home to five thousand

pounds stashed away and whatever value the boat retained.

There were plenty of possible scenarios. Get a little motor

boat and meander about on the French canals, after doing a

quick flit across the Channel in a flat calm. Day-sail in

convenient and enjoyable chunks down the coasts of France,

Spain and Portugal, past Gibraltar into the Mediterranean, in

a yacht. Or combine the two, cutting corners by joining the

canal system where convenient, yet still enjoying the

pleasure of sailing the easy or interesting bits.

Well, I'd always enjoyed sailing, and only found it really

hard going when I made stupid mistakes, usually caused by not

thinking things through properly beforehand. I started

talking about the options, and as always when you talk about

possibilities, they started to become clearer, and much more

practical.

Spend fifty pounds on a couple of books and a chart or two,

and the ideas turn very rapidly into pencil lines on paper,

and port-to-port voyages become stepped-off distances with

the brass dividers.

Study the pilot book on chill winter evenings, and dreams

quickly become wonderfully disturbing visions of hot summer

sunrises over recognisable cliffs and the shapes of distant

islands.

So I could buy the boat, quit my job in the spring of 2000

(what a year to do something dramatic and exciting!), and

then with all the books and charts, and after a winter-time

of thinking about it, decide on where I'd go. There wouldn't

be any no-go areas, except those due to the limits of my

abilities, or my confidence in the boat.

There were certainly plenty of boats about, inside my

price-range. I'd seen a delightful Macwester 26 in

Hullbridge, near Southend, which had everything I needed,

except that it had a petrol rather than a diesel engine, and

it was comfortably large enough for one or two people to live

aboard for a very extended period. With a shallow draft and

bilge keels, it could also go up the smallest creek and sit

happily on the mud. In addition, the autumn of 1999 was

coming on rapidly, and there would be plenty of other

suitable yachts for sale as the weather cooled. Given common

sense, fair sailing weather and reasonably good fortune, most

of those boats would get to most places with safety.

Obviously, something like that Macwester 26 wouldn't be a

good idea pitched up against a North Atlantic storm, but it

would be just fine cruising down any coast from Britain to

Spain in daily hops, and with the mast lowered onto the cabin

roof, it would potter safely and very happily along the

French canals to the Mediterranean. And with good forecasts,

and help from a crew of some sort to make voyages of more

than 100 miles or so, it could cheerful cruise the Med from

Gibraltar to Greece. Perhaps I could call on my nephew and

his mates, tough lads in their late teens, to spend some of

their holiday times with me when I needed watch-keepers.

As far as living costs were concerned, I knew that as a

born-again non-smoker - instant conversion, of course, after

a heart attack - my living costs could be ludicrously low if

I worked at it. For instance, buying absolutely all my food

on a credit card gave me a bill of around a hundred pounds a

month - add a couple of hundred for pocket money, drink and

odds and ends, and another hundred for boat costs like fuel

and maintenance, and the total came to four hundred pounds a

month. That's less than five thousand pounds a year.

Winter, of course, could be spent in some quiet marina or

tucked into a small harbour somewhere - perhaps five or six

months of mooring fees to be paid, but probably not too much

extra money gone. And eating Christmas pudding in shorts and

a tee-shirt had always appealed. If I managed to generate any

other income while away, that would be useful for either

enhancing the lifestyle or extending the period; otherwise I

could come home to virtually nothing, and the state would

provide - well, " sort-of ".

This last was an interesting side-light which I'd discovered,

more or less by accident. While paying in my community

charge, I had a brief conversation with one of the ladies on

reception at the council offices. " If I went away for a

couple of years, and came home pretty broke, how would I get

on for somewhere to live ? " I asked.

" We'd probably put you in a bed-and-breakfast

place, " she said, "and then one of the housing

trusts would try to find you something more permanent. "

" Just like that ? "

" Just like that, " she said. Then she grinned at

me. " I'd be gone, if I were you. "

One other factor which encouraged me - but totally amazed me

- was just how big my supporters' club was becoming.

Virtually everyone I mentioned the idea to said, " Stop

talking about it, just do it ", "I would if I

could, " or " Can I come with you ? " They

seemed to jump onto the idea with enthusiasm, and I tried to

track down the reasons behind this. After a great number of

discussions, I thought that it was simply a reflection of how

difficult many people find it to deal with the world we live

in. Employers want more and more from their workers, whatever

they do; relationships seem harder and harder to maintain,

and ordinary, hardworking and averagely intelligent people

like you and me find life increasingly difficult to cope

with.

Certainly the break-down of my own relationship, where I'd

thought I was quite secure and safe, had left me feeling

lonely, and concerned about my personal future. The job I was

doing was just that, a job, giving me an income in return for

my time. If you had the chance and the choice, and were

totally without major or unavoidable responsibilities,

wouldn't you opt to walk away ?

Probably the most vociferous and outspoken of the supporters

was my sister Jill, whose enthusiasm for the

idea, tempered with a constant little nagging doubt about my

actually having the courage to do it, probably helped more

than anyone else to get me going. She knew me too well -

easily sidetracked is one way of saying it. But after six

months of saying " I'm going to do it, " every time

we talked about it, I'd painted myself so far into a corner I

knew that I simply had to go anyway!

23 feet of glass fibre hull, with a big lump of lead hung

underneath and an alloy pole supporting nylon sails perched

on top of it, is not exactly how we choose to think of a

yacht. But the reality is that that's exactly what it is; a

complex amalgam of materials and stresses and strains,

brought together to make something which will face the sea

and survive, carry a small group of frail and not very

weather-resistant human beings about in relative safety, and

provide caravan-like comfort when in port.

Hopefully, that's what I've bought!

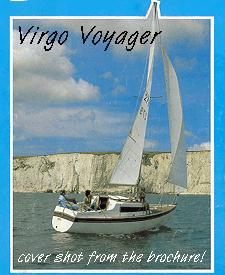

Pamela Jane is a 23ft Virgo

Voyager class sailing yacht build in 1979, with five

berths, twin bilge keels, and a 1993 15h.p. Nanni

twin-cylinder diesel engine. Although the advertising does

say she can accommodate 5 people, I wouldn't like to be one

of them; boats of this size are fine for a couple who get on

well, maybe with a child or two for weekends, but no more.

She has a white hull, yellow stripe just below the rubbing

strake, and yellow strips on her otherwise white coachroof.

It may sound horrible, but it looks okay . . .

Buying a boat is a pretty traumatic experience, as well as

being expensive.

There are hundreds on the market all the time, and dozens

within easy viewing reach of my base - the old firm must have

unknowingly spent quite a few pounds on supporting my travels

to boatyards around East Anglia. Every time you go to any

boatyard or marina, you see several for sale within the

budget, and many which are well over the top, but which you'd

nonetheless really like to buy. I really did look at a lot,

ranging from about 22 feet to 26 feet in length, and from

about £5,000 to £10,000 in price.

I rather fell in love with a couple before finding

Pamela Jane, but in each case there

was something a little suspect or unsuitable about them.

Probably the all-time favourite was a Samphire 23,

which was a proper little deep-keel, deep sea cruiser, quite

capable of major voyages in reasonable conditions, and

surviving reasonably in really bad weather.

But eventually . . . I found Pamela Jane purely fortuitously,

when trying to be a bit clever.

The nearest marina to my home was only about 5 miles away, at

Levington on the River Orwell in Suffolk. It

has its own semi-tame yacht brokerage, which runs a annual

"boat-sale" event, offering owners special deals for a

weekend which is well-publicised in the local and specialist

press. So I went to the marina a fortnight before the sale,

and there discovered Pamela Jane, with her then owners Graham

and Pamela on board, tidying up.

We spent a long time talking, and I had a really good look

around the little yacht - I was very impressed by the way

she'd been kept, and the attitude of her owners, who'd looked

after her carefully and lovingly. They also had a reassuring

survey report from this spring (April 99) which gave her a

sparklingly clean bill of health.

I suppose someone tougher-minded than me would have pushed

their price of £7,000 down a few hundred. But having seen

similar yachts for sale at much higher prices, and feeling

strongly that I would be getting a straight deal from a very

straight couple, I offered them their asking price through

the agent within a couple of hours of seeing the boat - I

went for a stride along the promenade at Felixstowe between

seeing the boat and offering the money. They accepted at

once, and I went back to the yacht for a cup of tea.